Nehru’s blunders that cost India dear

Nehru’s left-leaning ideology and his equations with Sheikh Abdullah could be the reason for his two blunders on China and Kashmir

Union minister KirenRijuju has done well to bring into public focus Jawaharlal Nehru’s mistakes in Kashmir as well as his handling of China policy. The blunders have cost India incalculably in blood, money, and prestige. Nehru had three gurus, namely, his father Motilal, Gandhi, and Krishna Menon. Motilal would have pointed out to his son that a quarter of India’s population was Muslim and an undivided sub-continent today could be well over 40 per cent. Until May 1947, it was not certain that there would be Partition. Jawaharlal was, therefore, modeled to lead Muslims; the Hindus were bound to fall in line behind a Brahmin willy-nilly. So much so, that even his wedding invitation card was printed in Urdu. This model came useful even after Partition for Nehru needed Muslims as the larger chunk of his vote bank. One has to recall that Sardar Vallabh bhai Patel was the Congress party’s unanimously elected choice to be its President and then Prime Minister.

In any case, Gandhi was the Congress’ role model for being pro-Muslim to the hilt. He even went to the extent of becoming President of the Khilafat Committee soon after World War I when the new reformist and revolutionary Turkish leader Kemal Mustafa as well as the victorious British dethroned and exiled the Caliph of all Sunni Islam and also the Sultan of the defeated Ottoman Empire. India had nothing to do with Turkey; indeed, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, then a prominent Congress leader-the day of his championing the Muslim separatist cause was still years away-kept away from the Khilafat Movement. But Gandhi would not be dissuaded from championing the cause of Islamic obscurantism.

Krishna Menon was the third in Nehru’s trinity of gurus. He was a closet communist whom Nehru leaned on for ideological guidance in defence and foreign affairs. It was he who convinced Nehru that China, a socialist country led by Mao Zedong would not clash with India on the battlefield. At most, it could differ on policy issues. In any case, India should project itself as a socialist power. That would match the country’s stance of being anti-imperialist in the light of its history, and be in tune with its aspiration to lead the Third World. This advice was music to Nehru’s ears. Little did Jawaharlal anticipate that in 1956, Britain and France would attack Colonel Nasser’s Egypt, and only a few months later Khrushchev’s Soviet Union would brutalize its satellite Hungary with tanks and guns. As a Third World leader and a personal friend of Nasser, India’s Prime Minister condemned the Anglo-French invasion in the bitterest of words. But Nehru was nonplussed when Hungary was attacked. He had to say something critical and therefore said: “Violence seldom solves anything. We hope that the dark clouds over Budapest would clear before long”. Ergo.

Similarly, the Indian prime minister was so taken aback by the Chinese aggression in 1962 that he was driven to tears while speaking on All India Radio: “My heart goes out to the people of Assam” he said. Nehru’s words conveyed the impression that Assam was lost. In Hindi, he said: “Assam khatremeinhai.”

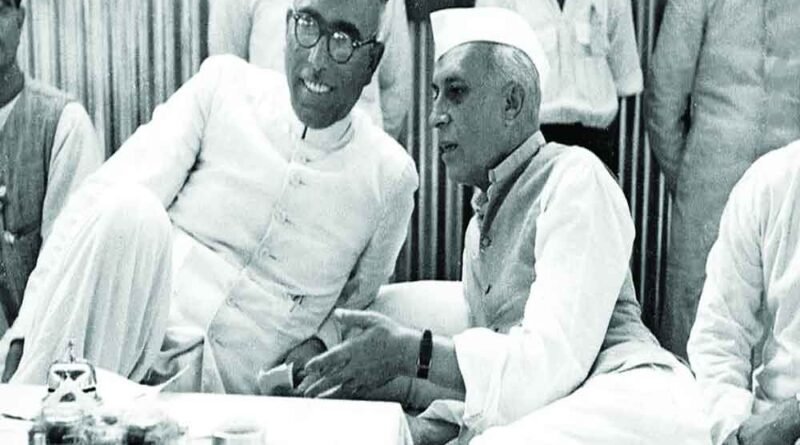

Jawaharlal Nehru’s blunders in Kashmir should be attributed to his friendship and fraternity with Sheikh Abdullah, the latter was popularly called “Lion of the Valley”. He was popular only among those who spoke the Kashmiri language. Once one crosses over to Muzaffarabad or Mirpur, where Punjabi is spoken, the Abdullah writ does not run. It was, therefore, the Sheikh’s advice to Nehru to not include those areas in his planning. Which, according to the late Prof. BalrajMadhok was the reason for India agreeing to a ceasefire, as it were, on the orders of the United Nations. That is how Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (POK) was born on the last midnight of 1948. The responsibility for obeying the United Nations was attributed to the last Viceroy Mountbatten.

Prof. BalrajMadhok, who grew up in Iskardu, where his father was in state service, consistently resented the fact that such personal likes and dislikes should influence national policies. Nevertheless, that was the beginning of the war of blood and money, which should conclude before long, with the abolition of Article 370. The idea of a separate flag and constitution for Kashmir was also Sheikh Abdullah’s insistence. To facilitate their introduction Article 370 was inserted as a Cabinet decision by Nehru. It never had the approval of India’s Parliament. Sheikh Abdullah was such a favourite of Nehru that when he was released from Tihar Jail, he was driven straight to the Prime Minister’s residence at Teen Murti, where he stayed until Nehru died. In contrast, Maharaja Hari Singh, who was disliked by the Sheikh, was dethroned and sent to Mumbai, although he remained a titular king of Kashmir.

Another of Nehru’s weaknesses was a contradiction between the animosity of Pakistanis, the ‘Kashmiryat’ of J & K, which had to be assuaged, and the Indian Muslims who had to be kept happy for their votes. As a result, it was difficult to think clearly and Nehru certainly did not do so. In the process, India’s national interests were dispatched to the backwaters of confusion.

(The writer is a well-known columnist, an author and a former member of the Rajya Sabha. The views expressed are personal)

Source: The Pioneer