How ancient manuscripts are writing the next chapter of India-UK cultural cooperation

When the Programme of Cultural Cooperation (PoCC) was signed between India and the UK in May 2025, it acknowledged that cultural heritage knows no borders.

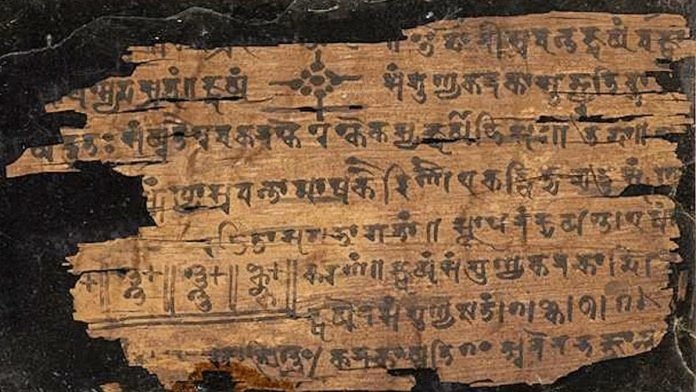

New Delhi, October 30, dmanewsdesk: A thrill ran down my spine as I looked at the Bakhshali manuscript, the first recorded instance of “0” being used mathematically as a number in its own right. This was at London Science Museum’s exhibition “Illuminating India: 500 Years of Science and Innovation” in 2018, as part of India-UK Year of Culture.

In an exhibition that was full of more visually appealing objects such as ancient astrolabes (intricate artwork in metal), surgical instruments based on Sushruta Samhita (the first treatise on surgery dating back to 6th century BCE) and prototypes of instruments and the camera used on India’s space mission to Mars, the unglamorous Bakhshali manuscript was the showstopper. Now housed in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the document was discovered in a field in Punjab in undivided India in 1881. Its discovery pushed back the history of modern mathematics by nearly 600 years, to the third or fourth century CE. Much of our hyper-digital world today rests on this notion of nothing, where the zero is the real hero.

Like the Bakhshali manuscript, deep in the bowels of the British Library and the Bodleian, ancient Sanskrit texts sit alongside Mughal court documents, and palm leaf manuscripts from Kerala rest near Tibetan ‘thangkas’ acquired during the colonial era.

Thousands of miles away in Chennai, Bengaluru, Patna and Lucknow, similar treasures lie in various states of preservation, some thriving in climate-controlled environments, others slowly crumbling to time’s winged chariot.

These are not merely historical artefacts. Manuscripts constitute the living memory of civilisations, the DNA of human knowledge, and increasingly, the foundation of one of the most ambitious cultural cooperation initiatives between India and the United Kingdom.

Manuscripts as museum of memory

When the Programme of Cultural Cooperation (PoCC) was signed between India and the UK in May 2025, it marked a fundamental shift in bilateral relations by acknowledging that cultural heritage knows no borders, and its preservation requires unprecedented collaboration. The digitisation of archives and manuscripts is first of the programme’s five key action areas and represents a paradigmatic and strategic shift toward democratising knowledge that has been locked away for centuries.

Consider the scale of this endeavour: India alone houses an estimated 5 million manuscripts spanning over 100 languages and scripts. Major British repositories together hold tens of thousands of manuscripts from India and in Indic languages. The Bodleian Libraries alone have about 8,700–9,000 Sanskrit and Prakrit manuscripts, the largest such collection outside South Asia. The British Library’s Oriental & India Office holdings include the India Office Records (over 14 kilometres of volumes) and a large collection of South Asian manuscripts, such as 1,000+ Jain manuscripts. The Wellcome Library houses around 6,500 Indic items, possibly the largest single collection of Sanskrit manuscripts outside of India, while Cambridge University Library maintains major Persian, Urdu, and South Asian holdings. Further significant caches exist in learned-society and museum collections catalogued through Fihirst (the UK union catalogue of manuscripts in Arabic script). Most of these are not digitised and therefore aren’t fully accessible to scholars and the broader public. Together, these collections represent one of humanity’s most comprehensive records of philosophical, scientific, literary, and spiritual knowledge.

From fragility to immortality

On the banks of the Ganga in Patna, the Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library is quietly waging a war against the trundle of time. With over 21,000 manuscripts, many in Persian and Arabic, the library has become a national hub for conservation, digitisation, and curative restoration. Elsewhere in the Mythic Society of Bengaluru, conservators race against the tide of time to digitise palm leaf manuscripts before humidity and age render them unreadable. At the 153-year-old Amir-ud-Daula Library in Lucknow, manuscripts in Turkish, Persian, Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Pali have found new life through complete digital transformation.

The Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) of the British Library is an excellent case study for the potential UK and India has in digitising and sharing our countries cultural heritage. EAP has digitised over 16 million images and over 35,000 soundtracks worldwide since 2004. Of more than 500 EAP projects globally, 95 are from India, accounting for almost a fifth of all projects.

A deeper dive into one of EAP’s major partners in India, the School of Cultural Texts and Records (SCTR) at Jadavpur University, reveals impact at both archival digitisation and systemic capacity building. The partnering has digitised thousands of fragile materials, from Bengali street literature to classical music recordings, and made them publicly available.

One of the projects digitised 2,980 titles of “popular market” Bengali books, including film song anthologies and folk manuals, into 96,973 images. Another major effort focused on early Bengali drama, digitising 249 titles across 385 volumes, yielding 1,12,174 images of rare printed and manuscript texts. One of the most remarkable projects under EAP-SCTR is preservation of around 2,780 tracks of North Indian classical music, totalling 1.1 terabytes of sound from private collections.

As one of EAP’s largest institutional partners in India, SCTR has helped shape the field of digital humanities and cultural informatics, not just by preserving the past, but by making it searchable, usable, and shareable.

Partnerships like these provide the blueprint for scaling collaboration exponentially under PoCC.

These are not isolated efforts but part of a growing recognition that digitisation is preservation’s most powerful ally.

For Indian, British and international scholars these repositories offer a trove of rare material.

India’s National Mission for Manuscripts (NMM), established in 2003, has already digitised over 350,000 manuscripts, with nearly 100,000 accessible online. The NMM will transition to the recently announced Gyan Bharatam Mission which aims to digitise millions of manuscripts with a Rs 60 crore investment.

The true revolution lies not in these impressive numbers, but in the collaborative framework emerging between Indian and British institutions.

The collaborative imperative

The PoCC proposes strengthening and speeding up partnerships between India’s institutions such National Archives of India, Gyan Bharatam and the UK ones such as the British Library. It aims to usher in a new model of cultural diplomacy that transcends historical fractures to focus on shared stewardship of human knowledge. This collaboration has the potential to involve:

- Joint cataloguing methodologies that will create the first comprehensive database of Indic manuscripts across both nations.

- Specialised OCR development for a range of Indic scripts, making ancient texts searchable and accessible.

- Exchange of scholarship in both directions that allows for decoding and translation to modern languages.

- Conservation technique and knowledge sharing that will benefit repositories in both countries.

- Creation of a global online manuscript platform connecting universities and scholars worldwide.

Democratising wisdom

The true power of this digitisation initiative lies not just in its preservation of the past, but in its democratisation of wisdom for the future. When a researcher in rural Rajasthan can access a 12th-century Ayurvedic text held in the Wellcome Collection, or when a student at Oxford can study original Buddhist manuscripts from Tawang, we witness the collapse of geographical and institutional barriers that have long restricted knowledge access.

This digital renaissance also addresses a critical challenge: The shortage of skilled personnel who can read ancient scripts. By creating searchable, transcribed digital versions, the PoCC seeks not just preserving manuscripts, it aims to make that knowledge accessible to scholars who may not have specialised linguistic palaeontology training, thereby expanding the community of people who can engage with this heritage.

Challenges as opportunities

The path forward is not without obstacles. The sheer diversity of languages, scripts, and materials requires unprecedented standardisation efforts and therefore costs. The technical challenges of creating high-quality digital images while maintaining accessibility demand innovation. Funding constraints and the digital divide threaten to limit access precisely where it’s needed most.

Yet these challenges represent opportunities for innovation. The development of AI-powered platforms for manuscript digitisation, as recently recommended by parliamentary panels, could revolutionise the field. The creation of multilingual, user-friendly interfaces could set global standards for cultural heritage access.

Writing the future

As we stand at this inflection point, the digitisation of manuscripts represents more than cultural preservation: It embodies a new form of soft power diplomacy, one built on shared knowledge rather than political expedience. The Programme of Cultural Cooperation’s emphasis on this initiative recognises that in our increasingly connected world, cultural heritage becomes most powerful when it’s most accessible.

The ancient palm leaf manuscripts of Kerala and the colonial-era documents of the India Office Collection are about to begin a new chapter of their existence: Written in ones and zeros, pixels and codes, accessible to billions rather than hundreds, preserved for millennia rather than decades. In this brave new dawn of a digital renaissance, India and the UK are not just preserving the past; we are democratising wisdom for a future that desperately needs the accumulated knowledge of ages.

Source: The Print