Digital refuge

In the build-up to the elections in Mizoram, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Telangana, the online presence of small but sane news platforms remains our source of solace and insight

I’m sixty-six and I can no longer remember the shape of an offline life. The internet became a regular part of my working day only when I turned forty-five. I was living in Brooklyn at the time and for the first time in my life, I had a non-dial-up cable connection and a laptop with a slot for a Wi-Fi card. The card didn’t come pre-installed with the iBook I reverently bought at the Apple Store in SoHo; I had to pay an extra $30 to have it fitted. After that, being online became a default part of living.

It’s odd that having lived without digital connectivity for more than two-thirds of my life, it’s an effort to recall the routines of that analog existence. As I write this sentence, I mentally shake my head at ‘analog’; normal life till the turn of the century now needs a distinguishing name. But it does because, amongst other things, the internet changed the way we absorb the world, particularly the news.

There was a time when the news consisted of the morning newspaper and All India Radio bulletins. If you were ambitious and willing to twiddle tuning knobs to catch distant radio stations on shortwave bands, the BBC’s World Service gave you an alternative view of the world. I was sixteen when the Yom Kippur war broke out and I remember it being written about in the Times of India and reported on the radio. The difference between radio then and now is that those vintage news bulletins didn’t make room for pundits; they didn’t discuss the news, they delivered it.

That Olympian, authoritative view of the world died with the digital transformation of our lives. I listen to podcasts for opinionated takes on things that interest me, from sport to books to politics. I grit my teeth and try to listen to podcasts that host opinions and views of the world that I disagree with, but the temptation of finding like-minded voices to murmur into my headphones as I walk around the park is irresistible and I end up curating for myself a bespoke view of breaking news.

One of the bonuses of the digital life for news obsessives is the number of sites on which you can read the same news. I spend a not inconsiderable part of my life trying to find workarounds that will let me tunnel under paywalls. There is a peculiar satisfaction in reading rich, right-wing newspapers for free. But this is not so different from the pre-digital habit of visiting a library and working through the dozen newspapers displayed on its racks. The difference now is the intersection between social media and news consumption.

This happens in two ways. The first is straightforward: I begin to follow people whose take on events interests me. I read their threads and click on the links they share. This has been emphatically the case with the war in Gaza because of the scarcity of news about the Palestinian experience of the war in Western newspapers and news platforms.

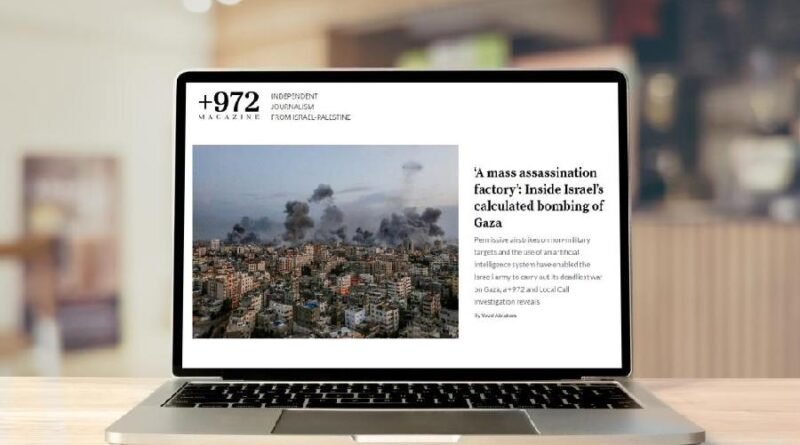

I wouldn’t have known of the detailed analysis that a site called +972 Magazine published on the way in which the Israel Defense Forces selects targets for aerial bombardment if it hadn’t been for the Twitter feed of someone I follow. It was fascinating to see how defence correspondents in the mainstream press were forced to acknowledge this detailed analysis of Israel’s use of Artificial Intelligence to generate targets to bomb, including purely civilian targets like apartment buildings and schools, once it began to circulate on social media, an analysis conspicuously missing from their own newspapers and magazines.

The second way in which social media has altered my consumption of the news is less useful. The writers and journalists that I used to know through their bylines and books are now knowable in less formal ways. I can follow them on ‘X’ (formerly known as Twitter) and on Instagram. The frankness with which otherwise sharp and prudent people reveal themselves on social media is something to behold. To read Simon Schama’s energetically one-eyed take on the slaughter in Gaza is to wonder where this fluent historian parks his empathy when it comes to the mass killing of non-Israeli women and children.

This snouting up of personal prejudice via social media is a bad way of following the news. While it gives you an insight into the biases of interesting and influential people, it also encourages you to dissolve the distinction between their hot takes on social media and their (generally) more considered pieces in print. Social media is a jungly undergrowth where people feel free to be the worst versions of themselves. The effort they make to brush their teeth and deodorise themselves when they appear in print should not be dismissed as deception; it is, often, the healthy result of exposure to sunlight, in this case, the public discourse of print.

The personalising of public discourse encouraged by social media is fascinating in the way that gossip columns are a swamp that sucks you in. One of the real differences between analog and digital news consumption is that in the latter you can disappear down a rabbit hole, pursuing some notional villain while wholly forgetting the big picture. On the other hand, social media’s ability to throw up links to first-rate articles and books and podcasts, published by small platforms, that you would never have heard of in the mainstream media makes negotiating the swamp worthwhile.

This is particularly true of the production and consumption of news in India where major newspapers, news channels and news agencies, with one or two exceptions (such as the paper you’re reading this in), have been reduced to hasbara factories, the Israeli word for justificatory propaganda.

In the build-up to the elections in Mizoram, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Telangana and in their aftermath, as votes are counted, results declared and explanations for victory and defeat proposed in servile and pandering news channels, the online presence of small but sane news platforms and magazines remains our source of solace and insight. The digital spiderweb that links us to these virtual islands of sanity almost makes our fumbling addiction to our phones worthwhile.

Author: Mukul Kesavan

Source: The Telegraph online