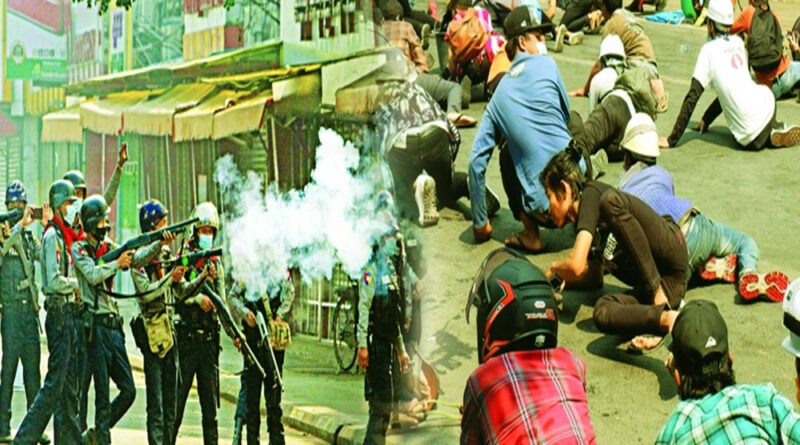

Tyranny continues in Myanmar

How India and the world should respond to the murderous atrocities unleashed by the military there on peaceful protesters

The emergency United Nations Security Council (UNSC) meeting on March 31, held at the United Kingdom’s initiative, to discuss the situation in Myanmar, has drawn a blank. This is clear from the statement issued after its conclusion by Britain’s permanent representative at the UN, Barbara Woodward, that the council would continue to “discuss the next steps”. Evidently, no steps were agreed upon, and mainly because of China. According to the Chinese mission at the UN, its permanent representative, Zhang Jun, had said in his statement: “China emphasises that all parties in Myanmar should take up the responsibility of maintaining national stability and development, act in the fundamental interests of the people, find a solution to the crisis within the constitutional and legal framework through dialogue and consultation, and continue to advance the democratic transition in Myanmar.”

The rest of the statement carries on in the same vein with a succession of platitudinous exhortations, completely overlooking the fact that it is Myanmar’s ruling junta that has unleashed a countrywide wave of murderous repression, while the multitudes demonstrating against the coup on February 1, 2021, have remained completely peaceful. Not surprisingly, his statement did not contain even a single word of condemnation of the junta’s actions. If anything, it was an effort to let the junta continue its savage repression while assuming a posture of virtuous neutrality.

One, of course, could not expect anything different from a regime that perpetrated the Tiananmen Square massacre of June 4, 1989, and is seeking to stamp out the cultural identity of the Uighurs of Xinjiang amid unspeakable atrocities. Nor can it be expected to do so in future, given its own autocratic orientation and the stakes it has acquired in Myanmar. Given its veto, it is unlikely that the UNSC will be able to take any effective step against the junta.

This, needless to say, is unfortunate. As Christine Schraner-Burgener, the UN special envoy on Myanmar, told the UNSC emergency session, the junta’s continuing savagery required a “firm, unified international response”. The question is what can countries like the US, Britain, members of the European Union and Australia do? The Biden Administration announced on February 11 the suspension of the 2013 Trade and Investment Framework Agreement, meant to boost bilateral business between the US and Myanmar, until the restoration of democracy there. It also imposed sanctions on 10 generals, some of them retired, who led the coup, and three commercial entities. Besides imposing restrictions on strategic exports, it has prevented the generals associated with the junta from improperly accessing the Myanmar Government’s funds of over $1 billion lying in the US.

The US Commerce Department placed under suspension on March 4, four military-controlled Ministries and conglomerates and, on March 22, the US Department of Treasury imposed sanctions on Myanmar’s police chief, a military commander, and two military units for their role in repressing demonstrators. Britain, Canada and New Zealand have also imposed sanctions and travel bans, and frozen assets. Australia had announced, on March7, the suspension of its limited cooperation with the Tatmadaw (as the Myanmarese Army is officially called) and said it would re-direct the aid marked for the Government to aid groups.

Sanctions, however, generally do not deliver much, and the ones imposed on the Tatmadaw earlier, did not. President Biden had perhaps this in mind when he said while announcing the first slew of sanctions in February: “We’ll be ready to impose additional measures and we’ll continue to work with our international partners to urge other nations to join us in these efforts.” Linda Thomas Greenfield, the US ambassador to the UN, articulated the same approach when, after hoping that the Tatmadaw would return to the barracks and allow the democratically-elected Government to take its place, she said that if it did not do so and continued with its attacks on civilian populations, “then we have to look at how we might do more”.

It remains to be seen what the US does, and with what effect. Meanwhile, India has also to look at its own role. While affirming its commitment to Myanmar’s transition to democracy, it has not condemned the junta. There are doubtless reasons for this. The junta has been closely cooperating with its efforts to counter the ethnic insurgent groups operating along its border with Myanmar. It has emerged as a significant seller of arms to the Tatmadaw and developed strong economic links with Myanmar. Besides, there is the compulsion to counter China’s growing influence there.

India, however, cannot remain silent indefinitely about the Tatmadaw’s stomach-turning cruelty. Besides, it has, as the world’s largest democracy, a moral responsibility to stand by those struggling to prevent its throttling in a neighbouring country. It must now speak out and stand with the other democracies in condemning what is happening next door. Fortunately, the Manipur Government has reversed its inhuman order to deny food and shelter-and even turn back- those crossing over to escape the junta’s savagery. India must do the opposite, and provide them with all the care it can.

(The author is Consulting Editor, The Pioneer. The views expressed are personal.)

Source: The Pioneer