When shade recedes

The plants gradually disappear from our consciousness, making us — to use Matthew Hall’s term — “plant-blind”, the human inability to notice plants in social settings

Though most pedagogy begins with fruits, whether it’s ‘a for apple’ or ‘a se anar, aa se aam, e se imli, ee se eekh’ or, in a slightly different kind of education, with ‘the fruit of forbidden knowledge’, the plants begin to disappear soon, pushed into books where they only have their kind for company. Or they gradually come to be ignored, like most such beings are, those who are not even considered worthy of a joke. (Who has ever laughed at the joke about a coconut falling on Newton’s head instead of an apple, for instance?) Like the jokes, even the proverbs and the grandmothers’ tales about plant life begin to sound moralising and, soon enough, without our awareness, they are pushed to the margins of our consciousness, just like our residential architectural designs force trees and plants to stand near the boundary walls of our houses.

It is as if it was the destiny of the plant form to arrive first, like it did in evolutionary history, before being forced to recede by new species such as human beings. An analogy for such a history can be found everywhere, even in our music. Take a song such as “Baago main bahar hain” (Aradhana) — the question about the plants in the garden and the health of the flower buds is turned into the likeness of a pickup line so that the more urgent questions about love and its confirmation between the lovers can be processed. Or another song of wooing — “Baharon phool barsaon mera mehboob aya hain” (Suraj); the flowers are summoned to do their bit, shower themselves on the beloved and, soon after, to bring colour to the painted designs on her hand, then forgotten, as plant forms usually are. It’s hardened into a habit, the invocation of flowers, occasionally a garden, and almost an immediate abandonment of this space for the imagined charm of the human social. “Phoolon ke rang se” (Prem Pujari) — for colour seems to be the most common expectation from the floral — is followed a little later with “Juhi ki kali tu” and, after the seemingly cursory nod to the plant world, exchanged for Petrarchan similes of romantic love.

The plants gradually disappear from our consciousness, making us — to use Matthew Hall’s term — “plant-blind”, the human inability to notice plants in social settings. This recession of a living form from our consciousness has many analogical histories — plants become borders and boundaries and backgrounds, in books, in architectural designs, in social conversation. In spite of all the footnotes that squat in our textbooks, we really don’t care why Shakespeare mentions the rose when he asks “What’s in a name” or when Robert Burns turns to the same flower when he has to liken his love to something; or why Satyajit Ray places two children amidst perennial grasses that are taller than them as a train spits smoke into the sky. That the history of England might be found in the history of the rose in the country, how the ‘Tudor rose’ brought two dynasties together in the fifteenth century and became the national flower, isn’t a whisper in our consciousness; nor does the awareness of the kaash phool having rhizomatous roots annotate our experience of Ray’s vision, which began with breaking the architecture of control that defines a human-centred world.

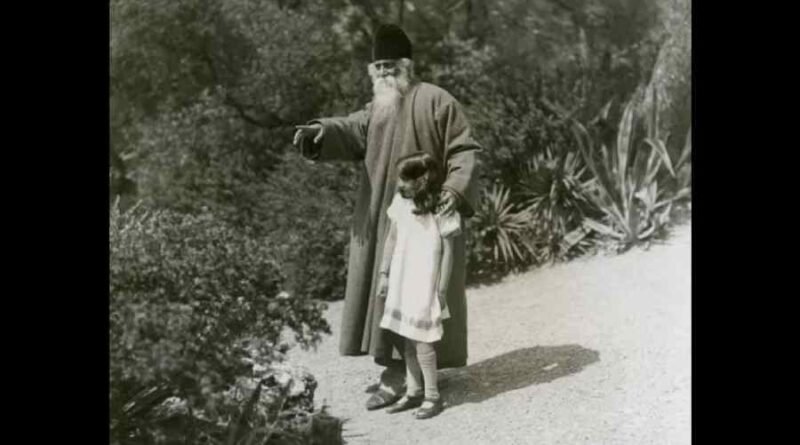

Even when the intention to stay with plants is purposive, as in “The Vegetation of the Earthly Garden”, a list of vegetation compiled by William L. Hanaway Jr. as an appendix to The Islamic Garden in 1976, there’s a tendency to lapse into a catalogue of the botanical where all is name and information: in alphabetical order, the list begins with anar and moves through badam, chinar, gul, limu, murd, nargis, sunbul, tuba to yasmin, with English translations of the words and their figurative meanings. Such lists, even when they aim to capture a cosmos, have the character of a survey. What if the encyclopedic impulse were replaced by one that is based on cohabitation, the knowledge of one’s plant neighbours, a relationship documented through suggestion, digression, divagation, these patterns of thought that derive from the architecture of trees themselves? Rabindranath Tagore, who privileged a sensory pedagogy over one that was tautly bookish, created a primer for students in his school that, in forcing them to notice the behaviour of plants as they changed with the seasons, turned them into detectives of the natural world. There’s also something else — by pushing a child to record their autobiography through this sensory world, where weather is more intimate than climate, such pedagogy, besides rehabilitating joy to a student’s life, might protect the humanities from lapsing into its moralising etiquette where a default pedagogy of the oppressed might be able to accommodate one where plant life is a playmate. Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, after cataloguing a list of trees — the madar, titpalla, bainchi, bonneyburo, banyan, pipal, akanda, laburnum — in the first page of his novel, Ichhamati, not from bureaucratic impulse but from affection and astonishment, ends by making a revolutionary statement: “Their voices, their stories, are the real history of our nation.” It’s a nudge towards a pedagogical model that the Indian nation could have chosen.

It might be the depletion and the deprivation of trees and their shadows from our lives that is compelling a new cinematic energy towards the continuation of philosophical botany that begins with an invocation of an unverifiable belief that we are composed of plants like the alphabet is. It has been appearing in unexpected locations — in the comedy behind the obsession with jackfruit in Kathal and with bottle gourd in Panchayat; the sideward glance on the plant that helps Rajkummar Rao in his investigations in Hit: The First Case; the living forest in Kantara; the nod to organic farming in Life Hill Gayi and Laapataa Ladies, where we also have the floral cosmology in the names of Phool, Pushpa, Pankaj, Suryamukhi, and Pushpa Travels. “You’ve turned us all into bees,” says Manju Mai to the young Phool in the film. How luscious it would be to have a pedagogy that could turn us into bees.

Poet and Author : Sumana Roy

Source: The Telegraph online