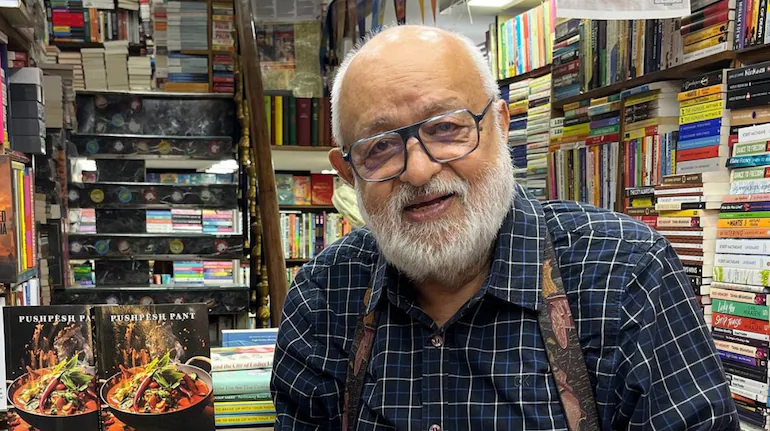

Myth of Mughlai, tyranny of tandoor & curse of curry are a blight on Indian food history: Pushpesh Pant

New Delhi, July 03, dmanewsdesk: “The Mughals didn’t come to India as emperors,” says food historian Pushpesh Pant, as we talk about his latest chronicle of Indian food stories and recipes – Lazzatnama. The only indulgent imperial dish that can be attributed to the Mughals, he adds, is the Lazeeza khichchdi. “The moment you say Mughalia food, what is Mughalia food? What we talk about as Mughalia food is actually post-Mughalia,” he explains.

Pant also has little love for the people-pleaser biryani, adding that the marketing hype is such that it has birthed new variants like the Moradabadi Biryani which was not even available in Moradabad till a decade or so ago. Instead, Pant says, Yakhni Pulao – with the rice cooked in meat stock – is the real deal. “Biryani to my mind is ostentatious… I don’t want to be told how much effort has gone into it!”

Pant’s knowledge of Indian food is experiential and encyclopaedic. As we talk, he conjures visions of dishes from Kashmir to Kanyakumari, vegetarian and non-vegetarian, technical as well as simple, well-known and little-known.

Cooking techniques, mediums and influences are discussed too. Talk of stuffed vegetable preparations like dum ki bhindi and chooran ke karele segways into vegetarian mussalams (including a “brilliant lauki lazeez mussalam”). “Kashmiri kadu ka Rogan Josh” and other vegetarian versions of meaty preparations are unpacked with relish.

In this interview with Moneycontrol, Pushpesh Pant also presents the idea that Mughlai food, which is often conflated with Indian khaana abroad, is an anachronistic invention that was lapped up by the British in the aftermath of the first war of Independence. Excerpts from the interview:

Your new book ‘Lazzatnama’ talks about foods from different parts of the country. Tell us about the title: why does deliciousness need a book of its own?

I think the ‘nama’ part explains this. Lazzat is something that everyone can taste. You can taste the flavours of the food. And the title is a gift from Rupa Publishers who always wanted the stories about food to be told along with recipes. So ‘nama’ is the chronicle of ‘lazzat’, which is foods and flavours, delicious morsels. So ‘Lazzatnama’ is a complete package that talks to you about recipes, their domain, their geographical indicators but at the same time takes you backstage about the legends and folklore – some real, some marketing hype – but all in all a very flavourful offering.

‘Delicious morsels’ is a great descriptor for a lot of your writing – where you often talk about people and places through food.

You talked about travelling, meeting people, knowing, I think what happens is when food travels, like language of a speaker travelling in different parts (of the country) and settling there, it changes. It’s like the Mumbaiya Hindi – the Mawali Ghati phrases come there. Or you have the Bengali rounding off everything very sweet in exile in Lucknow or Allahabad (Prayagraj) or somewhere. Food is the best introduction to a community’s identity. Its preserved heritage. It is also, in a younger generation, who have not stayed in regions where their parents were born or grown up – they have gone to boarding schools, or professional schools, medical, engineering, they have gone to preparatory schools, coaching centres like Kota – and these people, when they come home, don’t spend enough time to get to know their own cuisines.

The younger generation has a great urge to search for its roots, so this search for roots is something which encouraged me and inspired me to do this book.

Could you share a food story, perhaps something that was difficult to put together for the book?

Actually, nothing was hard because people were so helpful. I remember a great chef from Lucknow called Mohammad Farooq who once told me something which is the truth: stark truth, but truth. He said all these stories about food… yeh raiison ke chochle hain, garibon ki rotiyan hain. The stories created about a food to make it sound more exotic, make it aspirational (for the moneyed), and at the same time the person who cooks can keep selling his wares.

The examples that he gave are fantastic. One is the kakori kebab, which is a melt-in-the-mouth delicate seekh that is done not in the tandoor but in a sigdi, and there are several stories. One says that there was a debauched nawab who had lost his teeth due to his excesses – culinary and sexual – and he could not masticate properly. So his bawarchi made for him a kebab which he could enjoy and thus the kakori was born. Another story says that the nawab saab of Kakori wanted to curry favour with the British officers so when the naab laat saab – the lieutenant governor – of Lucknow came visiting him, he got a pâté-like preparation done for him and thus was Kakori kebab born. But when I accompanied Mohammed Farooq to Kakori – the sleepy, dusty township near Lucknow, I realized the story was something very different. It was truly what Farooq was leading up to is that there is an old Dargah of a Sufi saint. And from generations, elderly pilgrims have been coming to do Ziarat at this dargah and they of course had lost their teeth – not because of debauchery, not because they were Europeans who could not masticate Indian food with a bite, but they were old people who needed some kind of comfort food and thus the Kakori was created for these pilgrims at the Sufi Dargah which they enjoyed tremendously.

How many different parts of India do you touch upon in the book?

The book ranges all across, from Kashmir in the north to Kerala in the south. And from the east, some selections from North-Eastern states also, Bengal, Odisha, to west to Maharashtra, Gujarat, Deccan, coastline. We have tried to include at least one representative recipe, a signature dish from each part of the country.

Now, some parts of the country obviously have enjoyed a reputation for being a mecca of diners and gourmets. You have Awadh, for instance, you have Hyderabad, for instance. You have Delhi and Bhopal, you have Rampur. You have Banaras (Varanasi) for vegetarians, Jaipur for vegetarians. You have two different streams of cooking in Kashmir: the Pandit Wazwan and the Muslim Wazwan. Kerala is a small state but it has so many streams – it has Nadar, it has Namboodri, it has Syrian Christian, it has Moplah. And there is interesting food travelling all across the country.

There is a chapter on stuffed vegetable dishes in your book. To cite some examples from it, you have chooran ke karele from Hyderabad, Dum Ki Bhindi from Lucknow, begun ka launj from Banaras and Sambaria from Gujarat. It is an interesting way of looking at food, not just in terms of what the end product can be categorized as, but also the cooking technique of it. Can you talk us through how you organized the book?

I am a very lusty meat eater. But I have always thought about what do vegetarians enjoy the most? How do they find a delicacy which is worth talking about? Of course there are the dishes like Kathal ki Biryani, Kachche Kele ke Kabab, but what about the everyday fare which they eat? And somehow other we tend to overlook the plebeian vegetables which are everyday staple for people.

Now, take for instance, bhindi. If you have chooran ke karele, you also have chooran ki bhindi somewhere else because it is a stuffed vegetable. You slit the okra or the lady finger and you fill it up. But the spicing changes. Chooran ke karele has a spicing which does not lend itself to immediate adaptation in a bindi. But if you have a dum ki bhindi in Lucknow, it also is stuffed with spices – slightly different.

Then, if you are a Delhi wala and eat the tawe ki sabziya in Delhi, you would see that everything is there: there is a karela, there is a baingan, there is a bhindi, there is an aalu, there is arbi. These are vegetables which you use every day in your house but they are appearing here in an avatar which is slightly more exotic.

Stuffing a bhindi is not very difficult, packing a baingan is not very difficult. Karela is not everybody’s cup of tea, coffee or whatever you call it but some people like it. Some people like it bitter, (they) value it for its bitterness which is supposed to be therapeutic. But some like to pack it with filling which takes away the bitterness.

Now, if you come back to the origin of the vegetables which are filled up and packed, we go back to the coming of Armenians into India after political persecution in Armenia 500 years back. And what they did was they brought with them something called dolomades which became dolma in Lucknow – Karele ke dolme, tinde ke dolme, tamatar ke dolme – which is a vegetable packed with a tasty filling. So you have this whole which you can conjure up that how an international culinary stream influence came into our vegetables.

Interesting thing about vegetables is many vegetables which we take for granted as Swadeshi, are the part of the Columbian exchange (brought from another part of the world by Christopher Columbus), like the tomatoes, like the potatoes. Tamatar was once called bilayati begun in Bengal. There are sabzies which are totally Indian, like a pumpkin, like a lauki, like a ash gourd, and you could have these rendered in not necessarily in capsicum in a Sambariya in the Gujarati way, but you also have these rendered into mimicking a meat dish like the Kashmiri kaddu ka rogan josh or dum ki lauki. So you have different spicing, different cooking techniques and people can very easily do that.

You go to another section in the book which is the section not on vegetables but on mussalams. A mussalam is a dish which is intact and whole. Everybody talks about Murg musallam and there is a wild story about how there is a camel musallan which has a bakra inside it. And the bakra has a murg inside it and the murg has an anda inside it, and when you cut through the anda you get a small dried fruit, et cetera. And this is all packed in a bed of biryani. But if you go to the vegetarian musallams, you’d see that in Awadhi kitchen there is a brilliant Loki Laziz musallam which is served in a bed of very rich gravy. Or you even have a bandgobhi musallam, you have a phoolgobi musallam. So these musallam dishes are not talked about very often, but when you eat them, you suddenly realize that these are as good as a meaty musallam – a machhali musallam, murg musallam or ran musallam.

Gobhi musallam has two variations – you can do it with cauliflower, and you can do it with cabbage and both are different in texture and taste and appearance.

Both the musallam section and the vegetable section gave me great satisfaction to work.

Cabbage is something that one associates with kimchi or sauerkraut…

Or South Indian poriyals or stir fries of the Gujarati variety. But this one is steamed and packed with masalas and it is very very nice. I owe it to my mother and my sister who introduced me to the recipe. I think they had got it from a khansama who was very gifted in Rampur riyasat and who wanted to do it to please his vegetarian guests.

Do you see yourself as a food historian? Because in your writing there is a bit of food diplomacy, a bit of international relations, stories of how food travelled, who brought it where, there is food for the royals as well as the plebeian element of how people actually ate on the ground.

I don’t know if I can call myself a food historian. Because the moment you use the word historian, you impart it with a gravitas which I lack. I don’t have the discipline, I don’t have the academic rigour to systematically follow, footnote things. I mean there are people who are doing it. I have great respect for a gentleman name Doctor Kurush Dalal who is a professor of anthropology in Bombay University and he does this brilliantly.

I don’t think that most people who claim to be historians of food are historians of food. They just are describing food and buying without critically examining all stories which come to them about food and string them together. Like, you say Pulao came to India or so many Persian dishes like biryani came to India with Mughal badshah. A very nice author, Salma Hussain, whom I respect very greatly, says so. But come to think of it, did the Mughals come to India as badshahs?

Poor Babur was given a title of Badshah in Samarkand but Samarkand was a piddly little principality, no Badshahiyat involved there. And he was chased out of his family inheritance by his uncles. And he ran and came to India, not as a badshah but as an exile. Did not live long to become an emperor. His successors became emperors in India.

So no imperial dish came with Mughals from Persia or anywhere else. They became emperors in India.I have a theory that the myth of Mughalia, tyranny of tandoor and the curse of curry is the blight of Indian food history. The moment you say Mughaliya food, what is Mughaliya food? Humayun was chased out of his throne by Sher Shah Suri. Akbar inherited the throne at the age of 13; shifted capital from Delhi after his encounters with Hemu Bakkal to go to Agra. He was a Sufi-like character – his food was not Mughaliya and he was a very frugal eater. He was vegetarian for three days in a week and had khichdi very often. His son Jahangir drank himself to death; (he) was of course influenced by his Persian wife Noorjahan but not known to have created food. Now Shahjahan spent most of his time building stuff and producing children. I mean his wife Mumtaz Mahal died giving birth to his 14th child, and the poor man was made a prisoner by his son. So where is the Mughlai food? And his son Aurangzeb was a puritanical orthodox spartan Muslim who only loved khichdi. In one of his letters, he wrote to his son, “Please send me the Bavarchi who cooked for me such nice khichdi.” The son did not oblige. We do not know if he did that. Buthis khichdi, which Salma Hussain mentions is the Laziza, is the only Mughal dish which seems to have exotica and elements which are, shall we say, imperial. It is not the sick man’s khichdi, it is not the child’s or old man’s khichdi. It is a delicacy.

But the short point is what we today call Mughalia food is really post-Mughalia food. Some Mughal emperors who were living on the pensions of the British, after the British took over control of Delhi in the first decade of the 19th century, 1803… they ran away from Delhi and took shelter in Awadh. When they came back, they had imbibed some taste of Lucknow and after 1857 when Delhi was devastated, most cooks went away from Delhi to safer pastures and havens like Rampur to Patiala to nearby places where the British could not hound them. The British were hounding the Muslims because they had rallied round Bahadur Shah Zafar… when these people returned, in the first decade of the 20th century, the myth of the Mughal cooking was created. Everybody was claiming that he was Shahjahan’s royal bawarchi and so on, including Karim, whose historical documentation is that he started by selling aloo-gosht and roti on a pushcart. But then you then you invent a past, a legacy, which is imperial. It suited the British perfectly because they were claiming to be inheritors to the mantle of the Mughal emperor. Unka Iqbal isi liye buland tha (That’s why their confidence was high). So they supported the myth ki inka khana hamara khana hai, dilli ka khana Mughalia khana hai (their food, the food of Delhi is Mughlai food). But the food which really evolved beautifully, and everybody traces Mughal influence into it, is khana in Hyderabad, khana in Bhopal, khana in Rampur and the khana in Lucknow continued. Now all this is the Mughal Muslim food.

Now if you talk in terms of Kashmiri food, it predates (Mughlai). It goes back to the days of Sikandar and the first lot of Persians coming and settling down as carpet weavers, as woodworkers, as cooks in the Valley of Kashmir. They owe nothing to the Mughals.

Similarly, if you talk in terms of the vegetarian cooking traditions, you have food in Banaras and food in Jaipur and food in Jodhpur and food in Udaipur which has nothing to do with Mughals. Jaipur has some influence because they had matrimonial alliances with Delhi.

Take a case like Southern India, where the Mughals did not have any influence at all. Only poor Aurangzeb extended the frontiers, otherwise they stopped at the Deccan area – Aurangabad, Daulatabad – that was the limit they had reached. But if you come to that area, you see that the Arabs had come to southern India much before the advent of Islam and they had brought their halvas and their biryanis and their pulaos. So is everything is not Mughal (Mughlai).

I am not saying that everything is swadeshi, but I am saying that the Arabs came to India before the advent of Islam, so Arab influence is there, Abyssinian Habshi influences there. The coastal areas had influence from north, south, east, west, from Turkey and Persia and Awadh. So fine, it is as much Andhra, Telangana as maybe Madras Presidency as much as Marathwada, Maharashtra. If you look at the Nizams domain in Hyderabad, it touched upon north, south, east, west below Narmada beautifully and all food influences are there.

You have a fantastic story about Pulao in the book. Can you tell us about it, and which is better: Yakhni Pulao or Biryani?

Yakini Pulao is incomparable. I am biased in favour of yakhni pulao. Yakhni is flavorful meat stock, which the long grains of rice imbibe when they are cooked in it and the meat is cooked separately and when they are layered and put in dum, you have an exquisite dish.

Biryani to my mind is ostentatious. It is like a nouveau riche trying to display all its riches. And they insist on cooking it in basmati, so the poor basmati its aroma is gone. And you almost try to impress people by saying ki hamari artistic itani thi hamane kachche gosht Ki biriyani pakai thi. Jo 9/10th ghost paka tha, 9/10th chaval paka tha. We laid it and completed at the same time by applying heat from bottom and dum (steam) from the top (We cooked the meat and rice till they 9/10th done, layered them, and then finished the dish as a whole). So all that is fine but I don’t want to be told how much effort is gone into it. As they said the proof of the pudding is in the eating.

If you go to an old book, Abdul Halim Sharar’s ‘Lucknow, the Last Phase of the Oriental Culture’, he makes it very clear – this author was writing in the first decade of 20th century and he had lived in the court of Wajid Ali Shah in Metiabruz in Calcutta (now Kolkata). He was born after the 1857 Ghadar but he was aware of the memories of a devastated Delhi in terms of food. And he says ki Lucknow mein koi bhi aadmi biryani ko nahi khata hai, woh yakhni pulav khate hai (Noone in Lucknow eats biryani, they eat yakhni pulao). And they said that biryani is something like a malgoba, which is a mindless mélange of different ingredients. So I’m not changed my opinion.

Biryani is easier to sell because there is a great marketing hype about biryani. There’s a Hyderabadi kachche gosht ki biryani, dum ki biryani, Bohria biryani, Moplah biryani, Mattancherry biryani. Then you have a meen biryani, then you have a Calcutta biryani, now of course, Lucknow also is not to be left behind; they have Idris Miyan Ki biryani which is supposed to be very good. Then you have Dilli Ki biryani, you have Rampur ki biryani. Now you of course have a Moradabadi biryani, which is the latest kid in the block which is available both in vegetarian and non-vegetarian versions. I have been living in Delhi for past six decades and more and my hometown is in Nainital, Mukteshwar. So when we drove past, there were no such thing as a Moradabadi biryani even in Moradabad… Moradabadi biryani is of a very recent origin and Moradabad, incidentally, was not a riyasat. It was directly ruled by the British. It was famous for its brassware, not for its biryani – no way.

To answer your question more succinctly, pulao certainly came to India from Central Asia where it was called a pilaf. But pilaf is something which is a very simple dish. But what we eat in this country is an aromatic delicacy which has evolved, which you might say is the height of evolution of a pulao. And you have references to pulao in ancient Sanskrit texts like Bhava Prakash Nighantu which say pulao is rice cooked with condiments, meats and vegetables. So we knew pulao in the 4th century, 5th century AD. It was an Indian pulao, not a Persian pulao. Now if you have a Moplah biryani, it is closer to the Arab pulao than anything else.

The whole thing applies even to the vegetarian pulaos. It is not that the vegetarian pulaos were created for the vegetarians who were rich like Jain merchants, et cetera. If you see there is a fantastic pulao called Roz Billroz Vah Bill Tamar, which translates roughly as rice without condiments and without tamar which is tamarind. Now the Arabs called tamarind the dates of India. But this pulao was created for Molana Rumi, a great Sufi Saint who had forsaken meat but his mureeds, his disciples were very worried that his health would suffer, so they wanted to give him a nutritious pulao or a meal. They created a one dish pulao which was made with chickpeas for protein, supplemented for fiber with dates, apricots, dried figs, nuts of all kinds, and made creamy with melted butter poured on top of the boiled rice. Now this is a fantastic pulao which is called Kabuli pulao. So I would much rather stay play around with pulaos than worry about ostentation biryanis.

Along with food stories, a lot of your book also have recipes in them. Now, given that food bloggers have been around for a really long time in India, where do you see the place of recipe books?

Recipe books will have a very long shelf life. That’s why I keep writing like scribble, scribble, scribble… Food bloggers to my mind are the latest generation of freedom fighters. They fight for a free food sampling everywhere. There are good food writers like Vir Sanghi, but they are not bloggers… The bloggers give you a recipe which is picked up from somewhere, which is neither tried nor tested. It is best on Instagram, for a short reel. It has the plug to ensure the next good meal. But the recipe has not been tried and tasted; it has been unquestioningly flung on the viewers. So I do think the printed book recipe has a much longer shelf life.

Finally, since you begin the book with a section on khichdis, what is your favourite khichdi recipe?

My favorite khichdi recipe is a simple one. It is an Arhar ki dal ki khichdi which I like in a one-is-to-one ratio of dal and chaval, which I like to eat with a very watery gravy of haldi pani gosht or haldi pani machh. This recipe was shared by a dear friend who is no more, Atul Rai, Prem Chand’s grandson… this is one of the most brilliant dishes for these sweltering summers. You have arhar ki khichdi, khili khili (dry, and every grain of rice distinct) not a mismatch, not a porridge-like thing. But this khichdi made with arhar ki dal, not moong ki daal, not masoor ki daal, and also eaten with a thin gravy – that is my comfort food.

Source: Moneycontrol