Why are we digging Rakhigarhi a 9th time? This Harappan site is a gift that keeps giving

The current excavation season aims to unearth the many land-use patterns within the limits of the seven mounds at Rakhigarhi and beyond.

On a bright sunny day, under a starkly azure sky, while I leaned against the wall of a Mazar—an enshrined tomb—atop a mound overlooking the vastness of the historic site of Rakhigarhi, a curiosity gripped my mind. “Why are we digging Rakhigarhi again?” I asked the excavation director, Sanjay Manjul. After all, the site had been subjected to systematic excavations for eight field seasons—between 1997-2000, 2012-2016, and 2021-22—each dig lasting two to five months or more. One would think that multiple excavation attempts are enough to holistically reconstruct the historicity of an archaeological site like Rakhigarhi in Haryana’s Hisar district. But the reality is that in archaeology, the cycle of revisiting and re-examination depends on the future possibilities of investigation that a site holds. And Rakhigarhi exhibits great potential.

The research objectives of each investigation and its subsequent findings, thus, are more important than the number of digs already conducted. For instance, other major settlements of the Indus Valley civilisation, such as Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa (now in Pakistan) and Dholavira in Gujarat’s Kutch district, have been subjected to extensive excavations for decades. Yet, archaeologists have only been able to scratch the surface of this great civilisation’s story. Hence, the answer to why we are excavating Rakhigarhi for the ninth time relies entirely on unearthing the known and unknown missing links.

Tapping into the known

Archaeological remains covering the villages of Rakhikhas, Rakhishahpur and their adjoining fields in Hisar, 150 km from New Delhi, are divided into seven archaeological mounds, from RGR 1 to RGR 7, according to archaeologist Amarendra Nath in his report, Excavations at Rakhigarhi. These mounds (heaps indicating buried settlements) have been part of the daily lives of locals who have established a connection by making them a part of their routine. Accustomed to finding Harappan artefacts such as seals, beads, and terracotta bangles, inhabitants of Rakhigarhi use these mounds for various purposes: Cremation/burial, grazing and even as cricket fields for the village tots. They have formed a connection not just with the archaeological remains but with the archaeologists too.

For decades, archaeologists, scholars and young researchers have wandered about in the villages and fields looking for broken potsherds and artefacts. The villagers are now aware that, like them, archaeologists view these mounds as sacred buried treasure—waiting to unearth it with a touch of their trowels.

The journey of archaeological investigation at Rakhigarhi started when archaeologist Suraj Bhan added this site to academic data in 1968-69 with his PhD dissertation, Prehistoric Archaeology of the Saraswati and Drishadvati Valleys. His report extensively emphasised exposed structures, typical Harappan-painted pottery and associated cultural material, which further grasped the academic attention of archaeologists. However, it was not until three decades later, in 1998, that the site was first subjected to scientific and systematic archaeological investigation. Amarendra Nath, former director of the Archaeological Survey of India’s Institute of Archaeology, led the investigation for three continuous seasons from 1997 to 2000 (Amerandra Nath, Rakhigarhi: A Harappan Metropolises in the Saraswati-Drishdwati Divide, Puratattva 28: 39-45).

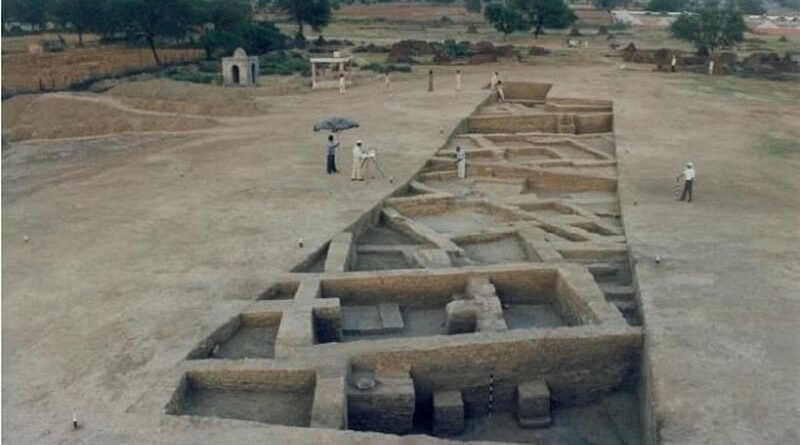

Six mounds, except mound RGR 3, were brought under investigation during the three field seasons. RGR 1 was labelled as the centre of lapidary (polishing, cutting and shaping of stone into decorative objects and jewellery) since large quantities of finished and unfinished beads, a high percentage of stone debitage, and a bead-making furnace were unearthed here. Harappan burials were excavated at RGR 7, whereas RGR 6 revealed an Early Harappan settlement. But the excavation of RGR 2 yielded some of the most striking evidence, such as fortification walls, podiums, fire altars and a matrix of streets and lanes interconnecting each other in the typical Harappan grid pattern. This excavation was certainly significant as it brought out primary data without which the following endeavours would have been incomplete.

Twelve years after this monumental feat, Rakhigarhi was re-examined by Professor Vasant Shinde of Deccan College for Post-Graduation and Research, Pune, between 2012 and 2016. This investigation focused mostly on four mounds, namely RGR 2, RGR 4, RGR 6 and RGR 7. The excavation at RGR-7 yielded the significant finding of ancient DNA from Harappan context, bringing a paradigm shift in the general understanding of the past and brought the question of ancient ancestry to the forefront.

Seven seasons–1997 to 2000 and 2012 to 2016—shifted the focus away from Mohenjodaro and Harappa, the most highlighted metropolises of the civilisation. Rakhigarhi’s initial findings placed it on an equal pedestal as the two former sites, which evolved from the ‘regionalisation era’, period denoted from c.5000 BCE to 2600 BCE (as per Robin Coningham and Ruth Young, Archaeology of South Asia: From Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE to 200 CE.) to to the ‘integration era’, the period denoted to the Mature Harappan period from c.2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. (J.G. Shaffer, The Indus Valley, Baluchistan and Helmand Traditions: Neolithic through Bronze Age

As per the published ASI report by Nath, there is a Pre -formative period of 5440 BP (BP= Before Present) followed by an Early Harappan period around 4570 BP and a Mature Harappan period around 3900 BP.

However, there were many aspects, such as the holistic understanding of the site plan known in the case of Dholavira, Banawali, Harappa etc. The intra-site and inter-site relation and the understanding of the land-use pattern remained unknown, not to mention unpublished data from previous endeavours made way for the eighth and now ninth season of the excavation.

Exploring the unknown

From 2021-2022, Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyay Institute of Archaeology and Excavation Branch II of ASI undertook excavation under Sanjay Manjul. The mound RGR 3, atop which the Mazar rests, was left unexcavated by the previous team. A roughly 13-meter-high mound scattered with pottery, numerous other artefacts and exposed Harappan brick structures gave an impression that it was an utmost significant piece in the larger jigsaw puzzle left incomplete.

The few trenches laid on the southern side during this excavation season (2021-2022) revealed a burnt brick and mud brick wall running around a residential complex with a brick-lined drain on the outside. The masonry of the wall and the finesse of mud brick made it clear to the team that this area held many answers.

Simultaneously RGR 1 was also brought under investigation. Evidence of a major street connecting by-lanes with workshops and residential complexes was found. Furnaces were the highlight. Working with mud-brick is never easy, and finding a mud-brick wall on either side of the street, enclosing a structural complex, was a moment out of a history textbook for me.

Debitage, finished and unfinished beads, hearths, etc., furthered knowledge about the craft activities at this site. But what was important was a complete unbroken stratigraphy of mound RGR 1, suggesting continuous, unbroken occupation from the Early Harappan period onwards.

However, it was RGR 7—denoted to archaeological remains buried in a privately owned field north of RGR 1—that pushed the established narratives. The initial thought of Manjul, following his discovery at Sinauli, was to further ancient DNA studies and establish a proper context for the burials. But just a level below the graves—close to 10 cm—evidence of earlier habitation was unearthed. In simple terms, it suggested that the area that was occupied by Early Harappans was abandoned at one point and later converted into a burial ground during the Mature Harappan period. “This means that the spread of Early Harappan deposit is much more expansive than once thought,” exclaimed Manjul after looking at the findings, possibly posing as the biggest early Harappan settlement.

Compared to the dry climate present-day Rakhigarhi deals with, the ancient site was rich with vegetation, and ‘paleochannels’ (remnants of ancient rivers and streams) of the Drishadvati drained the landscape. Present-day palaeoponds are relics of these paleochannels. The current season’s (2022-23) aim— in the light of new findings at RGR 7— is to unearth the many land-use patterns within the limits of these seven mounds and beyond. RGR 3 and RGR 1 are also under investigation during this field season which will help in understanding inter-site and intra-site dynamic. Only time (and trowels) will reveal the new facets of Rakhigarhi this season.https://68b1666d6a22dece9f4f87e01a4e324b.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-40/html/container.html

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)