New confusion over national monuments comes from a fixation on ‘who destroyed what’

Hindutva politics of heritage has not been able to resolve this conflict between ‘protection’ and ‘destruction’ so far.

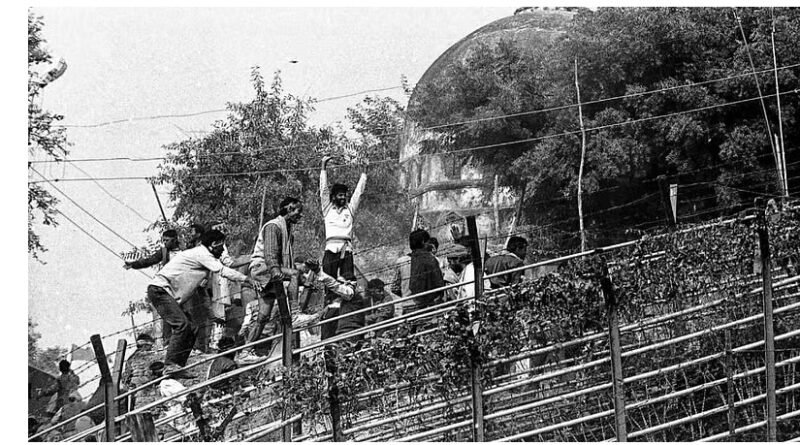

As a school student in 1986, I was fully confident that the Babri Masjid could not be demolished. I often argued with my friends that as a protected monument, the government would defend this mosque as its official duty. I had seen the Archaeological Survey of India’s typical blue-coloured board with the caption reading ‘Protected Monument’ installed at the entrance of every known historic site in Delhi. And I was under the illusion that all monuments had to be ‘protected’ as heritage buildings. Unfortunately, I was wrong. Babri Masjid was not a protected monument of national importance. Hence, the State as well as the political class did not have any legal or moral obligation in this regard.

The 1992 Babri Masjid episode, nevertheless, encourages us to ask a few basic questions, especially with regard to this deeply political idea of ‘national importance’: Who has the power to determine the national significance of a monument? What are the legal issues involved in this process? Is it legally possible to denationalise a protected monument?

These technical questions actually contribute directly to the debates on India’s national identity—something that is deeply embedded in our present political context.

Monuments and monumentalisation

In a very honest, objective, and highly informative article in Hindustan Times, Sanjeev Sanyal and Jayasimha K.R. highlight a few core problems associated with nationally protected monuments (NPMs). They identify four crucial issues: One, the inclusion of less important monuments in the national list; two, the incorporation of several moveable antiquities; three, untraceable monuments, and finally, a serious imbalance in the geographical distribution of the NPMs.

Sanyal and Jayasimha offer us an interesting set of policy-oriented solutions. First, the central government should define national importance. Second, it must de-notify the minor monuments and/or hand them over to state governments and independent agencies such as Delhi-based INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage). Third, moveable stand-alone antiquities must be shifted to designated and appropriate museums. Fourth, a systematic effort must be made to trace the missing NPMs. And finally, there should be a proper geographical/regional balance.

No one can deny the significance of these practical suggestions. However, heritage management is not as simple as it appears to be. Therefore, this crucial public intervention must be seen from a wider legal-political perspective.

Ruins and/or old historical buildings, we must remember, do not automatically become ‘monuments’ in India. There is a procedure through which historical buildings are converted into legally protected monuments of national importance. This legal recognition actually leads to the categorisation of monuments, their various listings, and practical aspects related to their adequate conservation. This is what I call the process of ‘monumentalisation’.

Sanyal and Jayasimha actually fail to understand the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act 1958 in its entirety. In fact, the suggestions they offer do not go against the existing legal framework.

Powers of the central government

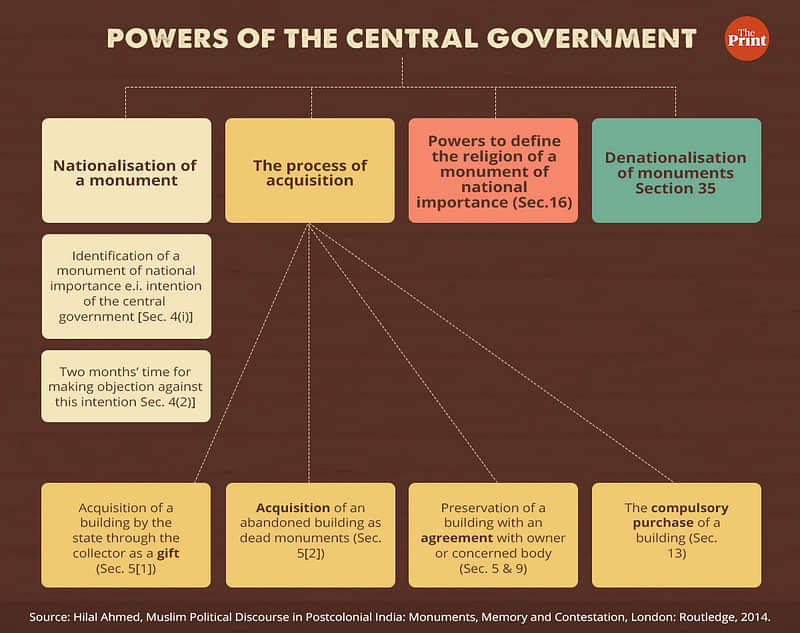

The 1958 Act, in principle, recognises the central government as the competent authority to define the concept of national importance in four different ways.

First, it authorises the government to select a few buildings and sites that are not protected as ‘monuments of national importance’ [Section 4 (1)]. Second, the Act empowers the government to acquire any historic buildings for preservation. Third, the Centre has the legal power to ‘denationalise’ the status of selected historical monuments [Section 35]. And finally, and perhaps most importantly, the central government has a right to determine the religious identity of a monument of national importance and the nature of religious observance inside it [Section 16 and Section 13(2)]. The following figure explains these powers.

Politics of national importance

This well-defined legal framework, it is important to note, offers immense possibilities to the political class to make use of it in a variety of ways. This is the reason why the idea of national importance has been one of the most contested questions in postcolonial India’s public life.

The Nehruvian State conceptualised national importance in a particular way. Nehru evoked two principles: Unity in diversity and history as an evolving enterprise for nation-building to define the monuments of modern India as enduring symbols. In a speech delivered at the centenary celebrations of the ASI on 14 December 1961, Nehru said: “In this highly utilitarian age, how does one justify archaeology?….There was a direct conflict between the claims of today in the sense of practical utility and the claims of the past…But it was inevitable that we should decide ultimately in favour of the present. And that turned out to be the best way of preserving the past also.” (J. L. Nehru 1964, Speeches, Vol. IV, 1957-63 New Delhi: Publications Division, GOI, p. 180).

This Nehruvian consensus survived for a long time. However, the Babri Masjid episode and the rise of radical Hindutva politics of heritage posed a serious challenge to it. The question such as ‘who built what’ was replaced with a politically motivated assertion ‘who destroyed what’. This significant change has also affected the discipline and practice of archaeology in recent years.

The conservation of a few ‘disputed’ monuments — especially the monuments built by Muslim rulers — is projected as a wastage of public money. Meanwhile, the excavation around these sites is described as an honest attempt to discover the original and undisputed history of India. The recent controversy over the Taj Mahal is the best example of this political attitude.

The Hindutva politics of heritage, in any case, is also facing a serious crisis now. It is very easy for radical groups to reject the Nehruvian consensus as an anti-Hindu project. The Mughal era monuments might conveniently be described as symbols of slavery and subjugation from their point of view. This kind of summary rejection, however, would be meaningless if it is not supported by a constructive policy for the conservation and protection of built heritage purely on the bases of archaeological and artistic considerations.

This is the main challenge and dilemma for Hindutva intellectuals. They have to produce a new imagination of national heritage. It should be in such a manner that the monuments, which do not have any direct political value, could be recognised as ‘monuments of national importance’ on the basis of universally applicable principles of conservation. At the same time, they have to adhere to the established political narratives of Hindu subjugation associated with a few known ‘disputed’ sites.

Hindutva politics of heritage, however, has not been able to resolve this conflict between ‘protection’ and ‘destruction’ so far.

Hilal Ahmed is a scholar of political Islam and associate professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), New Delhi. He tweets @Ahmed1Hilal. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

Source: Print