More trouble

As the number of COVID-19 infections soars, a triple mutant variant has emerged in Bengal

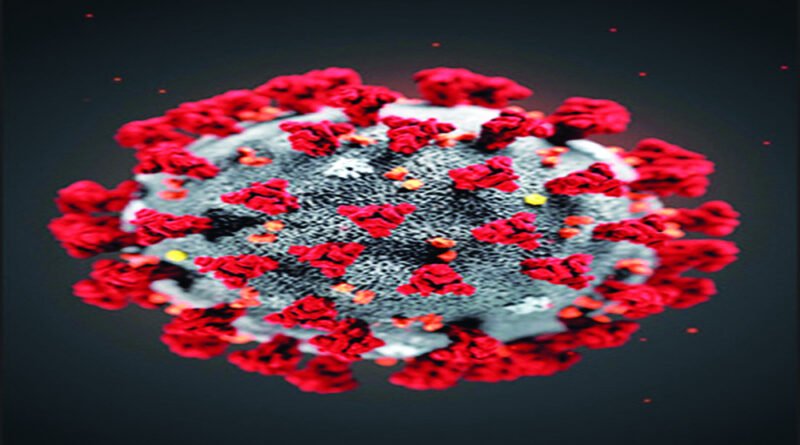

The humankind is facing an unprecedented crisis as the enemy is mightier than us — it frequently changes form and gets increasingly virulent — and arguably can render all our defences, including medicines and vaccines, ineffective. The Coronavirus is an RNA virus and all viruses have an inherent capacity to mutate. Basically, they mutate to stay on; but not all mutations are worrying for humans, save for the lethal ones. The main concern of the scientific community right now is the efficacy of the extant vaccines against the mutants and possible future variants. There is no way to stop the virus from mutating but the spectrum of vaccine effectiveness can be broadened keeping the possible mutations in mind. But as these changes in genes or protein sequencing cannot be predicted accurately, it’s next to impossible to gauge the future form of a current strain and therefore to develop an effective vaccine. Even as India struggles with a double mutant Coronavirus, there are reports that a new strain — a triple mutant variant — has been detected and is circulating predominately in West Bengal, the State where three more phases of Assembly elections are due and which had for long become the favourite hunting ground of politicians of all hues, none of whom cared for COVID-appropriate behaviour either for themselves or the electorate. Is there any end to these mutations, or will these keep haunting us forever?

There are worrying reports that even fully inoculated people have contracted the virus. Probably, they either didn’t adhere to COVID-appropriate norms during the interval between the doses, their bodies failed to produce antibodies despite getting vaccinated or the vaccine turned out to be ineffective (improper storage might be a cause). But if it is actually due to a new strain against which the existing vaccines are not working, the scientists and pharmaceutical giants need to put their heads together and find a solution. But scientific studies are data-based and not merely assumptive, while India has a huge sample size with a lot of variations. The onus is on the Government to encourage and adequately fund such studies that will help the scientific community in developing new vaccines. Another problem scientists across the world, and particularly in India, might face is if a person infected with a mutant strain shows symptoms similar to those of the precursor variant. In such a scenario, the existing vaccines will be futile and the variant will not be easily detected as only “genome sequencing” can give exact information about the strain afflicting a person. In a poor country like India, genome sequencing — which costs tens of thousands of rupees — is not an option for the majority. With a clutch of life-and-death questions hovering all around us, these future possibilities are needed to be worked upon in a “vision and mission” mode. Till we hit upon the correct answers, there is no option to wearing masks, sanitising hands and waiting in a queue for the jab while observing physical distancing.

Source: The Pioneer