Seeds of conflict

Turkish nationalism could only emerge at the expense of Muslim identity. For the Greeks, by contrast, religion continued to be a decisive factor in shaping their national identity

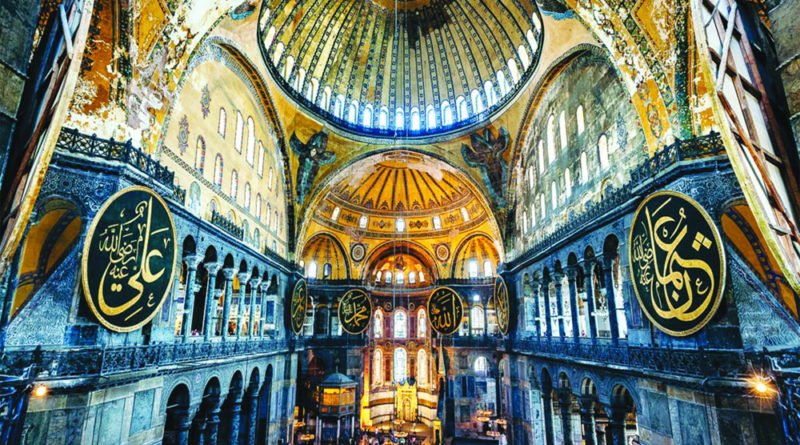

Edwin A Grosvenor (1845-1936), an American historian and author, who for some years lived and taught in Constantinople — as Istanbul was still called in the late 19th century — found that the Turks regarded Aya Sofia (Hagia Sophia) with “pride of conquest than affection.” The exquisite cathedral was still functioning as a mosque when Grosvenor wrote the history of the Ottoman capital in two volumes, Constantinople (1895). Nevertheless, since the end of the Crimean War (1854-56), its ground floor and the gallery were thrown open to the visitors for payment of a fee. The Christian characteristics of the cathedral were so pronounced that “its structural form has always resisted the requirements of Moslem ritual.”

The Turks, being conscious that “though the mosque is theirs, it is not of them”, had to import two distinctive symbols connected with the pulpit. The first was a pair of silken flags, “significant of victory of Islam over its parent faiths, Judaism and Christianity.” Second, every Friday, when its Sheikh (Imam) climbed the steep pulpit steps to preach, he held in his right hand an unsheathed sword, indicative of the manner in which the Hagia Sophia was conquered. “So, would the Moslem forget the long past of the church?” asked Grosvenor. “He cannot, for the flags and sword are there” (Constantinople, Vol-II, Pg, 543)

It is speculative whether the flags and sword would be reintroduced in Hagia Sophia, which was recently reverted to a mosque. Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, however, did not re-reclaim Hagia Sophia for Islam in a manner reminiscent of Sultan Mehmed II in 1453 AD. Erdogan achieved his end through a presidential decree, published in the official gazette on July 10. He has, thus, clothed himself in the role of “Gazette Ghazi.”

Mustafa Kemal Pasha, former President of Turkey, was also known as a “Ghazi” (vanquisher of infidels) for 14 long years before he adopted his last name Ataturk in 1935. This title was conferred upon him by the new Turkish National Assembly in September 1921, at the height of the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) that he led as the Field Marshal. To many of his countrymen, especially those who never saw him, the title conjured a glamourised image.

Once, when Kemal Pasha “Ghazi”, as biographer Patrick Kinross informs, was visiting a mountainous village in Turkey, he found that an artist had drawn his portrait from imagination on a wall. It was that of a formidable warrior, with sweeping moustaches and a seven-foot long sword. The villagers, however, were shocked to discover a clean-shaven Ghazi in European style summer suit, a sports shirt open at the neck and a Panama hat. So great was their disbelief that they barely managed to clap as the Ghazi walked past his imaginary portraiture. The conqueror was wearing the costume of the infidel (Ataturk: The Rebirth of a Nation, Pg, 414).

More than his western attire, Kemal’s westernising policy was likely to scandalise his countrymen, who had been direct subjects of the Caliphate for 400 years. However, it was much less than what we might assume. Kemal, by sheer force of his personality, no less than the weight of his achievements, was able to ramrod secularisation in matters of State policy and national life of Turkey. He abolished the Caliphate, eliminated religious courts, abolished the fez cap, discouraged veil for women, suppressed religious brotherhood, closed sacred tombs as places of worship, declared the Gregorian calendar as a national calendar, replaced Sharia with a new civil code law, introduced Latin alphabets in place of Arabic for writing Turkish and made the adoption of the last name mandatory (himself took up Ataturk) among others.

Even the name of the republic viz, Turkey (which citizens called Türkiye), clearly revealed its European origin. The term Turk, profoundly connected with Islam, had originally been given by the Europeans in the 11th century. Whether the modernisation of Turkey could have been achieved without brazen westernisation is a matter of opinion. However, through these measures, Ataturk built up a Turkish identity founded on language and territory but delinked from religion.

“In the imperial society of Ottomans, the ethnic term Turk was little used and then chiefly in a derogatory sense” says Bernard Lewis, “to designate Turcoman nomads or later ignorant and uncouth Turkish speaking peasants of Anatolian villages. To apply it to an Ottoman gentleman of Constantinople would have been an insult” (The Emergence of Modern Turkey, Pg 1-2). Until the 19th century, the Turks had thought of themselves purely as Muslims. Turkish nationalism could only emerge at the expense of Muslim identity. Ataturk’s republic, however, was one-party rule. Therefore, he could enforce his policies without any organised opposition. He did not banish religion from the republic but controlled its institutions, clergy and instructions through State apparatus.

For the Greeks, by contrast, religion continued to be a decisive factor in shaping their national identity. The Lausanne Convention on the compulsory exchange of population between Greece and Turkey (January 30, 1923) defined a Greek as one belonging to “Greek Orthodox religion” and Turk as “Moslem” without any reference to a person’s mother tongue. Greece’s democratic Constitution (2001) begins counter-intuitively “in the name of Holy and Consubstantial and Indivisible Trinity” rather than Solon, Clisthenes, Themistocles and Pericles.

The reason for the indissoluble bond between Eastern Orthodox Christianity and Greek identity is two-fold. First, during the Byzantine era (mid-fourth to mid-15th century AD) orthodox religion cemented spiritual and national unity of the Greeks. The Hellenic past of the Greeks witnessed conflict of philosophy and religion as well as extreme political disunity. Second, under the Ottoman rule (mid-15th century to 19th century), the Church formed the nucleus of the Greek nation. Under the millat system, the Greek patriarch based in Constantinople also acted as the secular head of the Roum millet (Roman nation) comprising all Christian subjects in the Ottoman empire. It, thus, functioned as a State within the Empire, whose influence continued to increase as Ottoman power declined vis-à-vis Europe.

The pioneer of the Greek War of Independence (1821-29) was Germanos, the Archbishop of Patras, who on April 4, 1821, proclaimed the insurrection against the Turks. Several high dignitaries of the Orthodox Church, including Patriarch of Constantinople Gregory IV himself, suffered martyrdom. Thus, Church and Greek independence somehow got interconnected from the beginning. This is a legacy that even 21st century Greece continues to respect. However, the Church and the State were separate even during the Byzantine Empire, with no scope for conflict between the Emperor and the Patriarch, unlike between the Pope and the monarchs in Latin Christendom. The same continues to be true in the republic of Greece, where the Church has no role in statecraft. Turkey, meanwhile, has dented its own image by reversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque.

(The writer is an author and independent researcher. The views expressed herein are personal.)

Source: The Pioneer